Having squeezed beneath the security gate, Robert Langdon now stood just inside the

entrance to the Grand Gallery. He was staring into the mouth of a long, deep canyon. On

either side of the gallery, stark walls rose thirty feet, evaporating into the darkness above.

The reddish glow of the service lighting sifted upward, casting an unnatural smolder

across a staggering collection of Da Vincis, Titians, and Caravaggios that hung

suspended from ceiling cables. Still lifes, religious scenes, and landscapes accompanied

portraits of nobility and politicians.

Although the Grand Gallery housed the Louvre's most famous Italian art, many

visitors felt the wing's most stunning offering was actually its famous parquet floor. Laid

out in a dazzling geometric design of diagonal oak slats, the floor produced an ephemeral

optical illusion—a multi-dimensional network that gave visitors the sense they were

floating through the gallery on a surface that changed with every step.

As Langdon's gaze began to trace the inlay, his eyes stopped short on an unexpected

object lying on the floor just a few yards to his left, surrounded by police tape. He spun

toward Fache. “Is that . . . a Caravaggio on the floor?”

Fache nodded without even looking.

The painting, Langdon guessed, was worth upward of two million dollars, and yet it

was lying on the floor like a discarded poster. “What the devil is it doing on the floor!”

Fache glowered, clearly unmoved. “This is a crime scene, Mr. Langdon. We have

touched nothing. That canvas was pulled from the wall by the curator. It was how he

activated the security system.”

Langdon looked back at the gate, trying to picture what had happened.

“The curator was attacked in his office, fled into the Grand Gallery, and activated the

security gate by pulling that painting from the wall. The gate fell immediately, sealing off

all access. This is the only door in or out of this gallery.”

Langdon felt confused. “So the curator actually captured his attacker inside the Grand

Gallery?”

Fache shook his head. “The security gate separated Saunière from his attacker. The

killer was locked out there in the hallway and shot Saunière through this gate.” Fache

pointed toward an orange tag hanging from one of the bars on the gate under which they

had just passed. “The PTS team found flashback residue from a gun. He fired through

the bars. Saunière died in here alone.”

Langdon pictured the photograph of Saunière's body. They said he did that to himself.

Langdon looked out at the enormous corridor before them. “So where is his body?”

Fache straightened his cruciform tie clip and began to walk. “As you probably know,

the Grand Gallery is quite long.”

The exact length, if Langdon recalled correctly, was around fifteen hundred feet, the

length of three Washington Monuments laid end to end. Equally breathtaking was the

corridor's width, which easily could have accommodated a pair of side-by-side passenger

trains. The center of the hallway was dotted by the occasional statue or colossal porcelain

urn, which served as a tasteful divider and kept the flow of traffic moving down one wall

and up the other.

Fache was silent now, striding briskly up the right side of the corridor with his gaze

dead ahead. Langdon felt almost disrespectful to be racing past so many masterpieces

without pausing for so much as a glance.

Not that I could see anything in this lighting, he thought.

The muted crimson lighting unfortunately conjured memories of Langdon's last

experience in noninvasive lighting in the Vatican Secret Archives. This was tonight's

second unsettling parallel with his near-death in Rome. He flashed on Vittoria again. She

had been absent from his dreams for months. Langdon could not believe Rome had been

only a year ago; it felt like decades. Another life. His last correspondence from Vittoria

had been in December—a postcard saying she was headed to the Java Sea to continue her

research in entanglement physics . . . something about using satellites to track manta ray

migrations. Langdon had never harbored delusions that a woman like Vittoria Vetra

could have been happy living with him on a college campus, but their encounter in Rome

had unlocked in him a longing he never imagined he could feel. His lifelong affinity for

bachelorhood and the simple freedoms it allowed had been shaken somehow . . . replaced

by an unexpected emptiness that seemed to have grown over the past year.

They continued walking briskly, yet Langdon still saw no corpse. “Jacques Saunière

went this far?”

“Mr. Saunière suffered a bullet wound to his stomach. He died very slowly. Perhaps

over fifteen or twenty minutes. He was obviously a man of great personal strength.”

Langdon turned, appalled. “Security took fifteen minutes to get here?”

“Of course not. Louvre security responded immediately to the alarm and found the

Grand Gallery sealed. Through the gate, they could hear someone moving around at the

far end of the corridor, but they could not see who it was. They shouted, but they got no

answer. Assuming it could only be a criminal, they followed protocol and called in the

Judicial Police. We took up positions within fifteen minutes. When we arrived, we raised

the barricade enough to slip underneath, and I sent a dozen armed agents inside. They

swept the length of the gallery to corner the intruder.”

“And?”

“They found no one inside. Except . . .” He pointed farther down the hall. “Him.”

Langdon lifted his gaze and followed Fache's outstretched finger. At first he thought

Fache was pointing to a large marble statue in the middle of the hallway. As they

continued, though, Langdon began to see past the statue. Thirty yards down the hall, a

single spotlight on a portable pole stand shone down on the floor, creating a stark island

of white light in the dark crimson gallery. In the center of the light, like an insect under a

microscope, the corpse of the curator lay naked on the parquet floor.

“You saw the photograph,” Fache said, “so this should be of no surprise.”

Langdon felt a deep chill as they approached the body. Before him was one of the

strangest images he had ever seen.

The pallid corpse of Jacques Saunière lay on the parquet floor exactly as it appeared in

the photograph. As Langdon stood over the body and squinted in the harsh light, he

reminded himself to his amazement that Saunière had spent his last minutes of life

arranging his own body in this strange fashion.

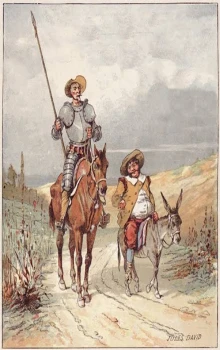

Saunière looked remarkably fit for a man of his years . . . and all of his musculature

was in plain view. He had stripped off every shred of clothing, placed it neatly on the

floor, and laid down on his back in the center of the wide corridor, perfectly aligned with

the long axis of the room. His arms and legs were sprawled outward in a wide spread

eagle, like those of a child making a snow angel . . . or, perhaps more appropriately, like

a man being drawn and quartered by some invisible force.

Just below Saunière's breastbone, a bloody smear marked the spot where the bullet had

pierced his flesh. The wound had bled surprisingly little, leaving only a small pool of

blackened blood.

Saunière's left index finger was also bloody, apparently having been dipped into the

wound to create the most unsettling aspect of his own macabre deathbed; using his own

blood as ink, and employing his own naked abdomen as a canvas, Saunière had drawn a

simple symbol on his flesh—five straight lines that intersected to form a five-pointed star.

The pentacle.

The bloody star, centered on Saunière's navel, gave his corpse a distinctly ghoulish

aura. The photo Langdon had seen was chilling enough, but now, witnessing the scene in

person, Langdon felt a deepening uneasiness.

He did this to himself.

“Mr. Langdon?” Fache's dark eyes settled on him again.

“It's a pentacle,” Langdon offered, his voice feeling hollow in the huge space. “One of

the oldest symbols on earth. Used over four thousand years before Christ.”

“And what does it mean?”

Langdon always hesitated when he got this question. Telling someone what a symbol

“meant” was like telling them how a song should make them feel—it was different for all

people. A white Ku Klux Klan headpiece conjured images of hatred and racism in the

United States, and yet the same costume carried a meaning of religious faith in Spain.

“Symbols carry different meanings in different settings,” Langdon said. “Primarily, the

pentacle is a pagan religious symbol.”

Fache nodded. “Devil worship.”

“No,” Langdon corrected, immediately realizing his choice of vocabulary should have

been clearer.

Nowadays, the term pagan had become almost synonymous with devil worship—a

gross misconception. The word's roots actually reached back to the Latin paganus,

meaning country-dwellers. “Pagans” were literally unindoctrinated country-folk who

clung to the old, rural religions of Nature worship. In fact, so strong was the Church's

fear of those who lived in the rural villes that the once innocuous word for

“villager”—villain—came to mean a wicked soul.

“The pentacle,” Langdon clarified, “is a pre-Christian symbol that relates to Nature

worship. The ancients envisioned their world in two halves—masculine and feminine.

Their gods and goddesses worked to keep a balance of power. Yin and yang. When male

and female were balanced, there was harmony in the world. When they were unbalanced,

there was chaos.” Langdon motioned to Saunière's stomach. “This pentacle is

representative of the female half of all things—a concept religious historians call the

‘sacred feminine' or the ‘divine goddess.' Saunière, of all people, would know this.”

“Saunière drew a goddess symbol on his stomach?”

Langdon had to admit, it seemed odd. “In its most specific interpretation, the pentacle

symbolizes Venus—the goddess of female sexual love and beauty.”

Fache eyed the naked man, and grunted.

“Early religion was based on the divine order of Nature. The goddess Venus and the

planet Venus were one and the same. The goddess had a place in the nighttime sky and

was known by many names—Venus, the Eastern Star, Ishtar, Astarte—all of them

powerful female concepts with ties to Nature and Mother Earth.”

Fache looked more troubled now, as if he somehow preferred the idea of devil

worship.

Langdon decided not to share the pentacle's most astonishing property—the graphic

origin of its ties to Venus. As a young astronomy student, Langdon had been stunned to

learn the planet Venus traced a perfect pentacle across the ecliptic sky every four years.

So astonished were the ancients to observe this phenomenon, that Venus and her pentacle

became symbols of perfection, beauty, and the cyclic qualities of sexual love. As a tribute

to the magic of Venus, the Greeks used her four-year cycle to organize their Olympiads.

Nowadays, few people realized that the four-year schedule of modern Olympic Games

still followed the cycles of Venus. Even fewer people knew that the five-pointed star had

almost become the official Olympic seal but was modified at the last moment—its five

points exchanged for five intersecting rings to better reflect the games' spirit of inclusion

and harmony.

“Mr. Langdon,” Fache said abruptly. “Obviously, the pentacle must also relate to the

devil. Your American horror movies make that point clearly.”

Langdon frowned. Thank you, Hollywood. The five-pointed star was now a virtual

cliché in Satanic serial killer movies, usually scrawled on the wall of some Satanist's

apartment along with other alleged demonic symbology. Langdon was always frustrated

when he saw the symbol in this context; the pentacle's true origins were actually quite

godly.

“I assure you,” Langdon said, “despite what you see in the movies, the pentacle's

demonic interpretation is historically inaccurate. The original feminine meaning is

correct, but the symbolism of the pentacle has been distorted over the millennia. In this

case, through bloodshed.”

“I'm not sure I follow.”

Langdon glanced at Fache's crucifix, uncertain how to phrase his next point. “The

Church, sir. Symbols are very resilient, but the pentacle was altered by the early Roman

Catholic Church. As part of the Vatican's campaign to eradicate pagan religions and

convert the masses to Christianity, the Church launched a smear campaign against the

pagan gods and goddesses, recasting their divine symbols as evil.”

“Go on.”

“This is very common in times of turmoil,” Langdon continued. “A newly emerging

power will take over the existing symbols and degrade them over time in an attempt to

erase their meaning. In the battle between the pagan symbols and Christian symbols, the

pagans lost; Poseidon's trident became the devil's pitchfork, the wise crone's pointed hat

became the symbol of a witch, and Venus's pentacle became a sign of the devil.”

Langdon paused. “Unfortunately, the United States military has also perverted the

pentacle; it's now our foremost symbol of war. We paint it on all our fighter jets and hang

it on the shoulders of all our generals.” So much for the goddess of love and beauty.

“Interesting.” Fache nodded toward the spread-eagle corpse. “And the positioning of

the body? What do you make of that?”

Langdon shrugged. “The position simply reinforces the reference to the pentacle and

sacred feminine.”

Fache's expression clouded. “I beg your pardon?”

“Replication. Repeating a symbol is the simplest way to strengthen its meaning.

Jacques Saunière positioned himself in the shape of a five-pointed star.” If one pentacle is

good, two is better.

Fache's eyes followed the five points of Saunière's arms, legs, and head as he again ran

a hand across his slick hair. “Interesting analysis.” He paused. “And the nudity?” He

grumbled as he spoke the word, sounding repulsed by the sight of an aging male body.

“Why did he remove his clothing?”

Damned good question, Langdon thought. He'd been wondering the same thing ever

since he first saw the Polaroid. His best guess was that a naked human form was yet

another endorsement of Venus—the goddess of human sexuality. Although modern

culture had erased much of Venus's association with the male/female physical union, a

sharp etymological eye could still spot a vestige of Venus's original meaning in the word

“venereal.” Langdon decided not to go there.

“Mr. Fache, I obviously can't tell you why Mr. Saunière drew that symbol on himself

or placed himself in this way, but I can tell you that a man like Jacques Saunière would

consider the pentacle a sign of the female deity. The correlation between this symbol and

the sacred feminine is widely known by art historians and symbologists.”

“Fine. And the use of his own blood as ink?”

“Obviously he had nothing else to write with.”

Fache was silent a moment. “Actually, I believe he used blood such that the police

would follow certain forensic procedures.”

“I'm sorry?”

“Look at his left hand.”

Langdon's eyes traced the length of the curator's pale arm to his left hand but saw

nothing. Uncertain, he circled the corpse and crouched down, now noting with surprise

that the curator was clutching a large, felt-tipped marker.

“Saunière was holding it when we found him,” Fache said, leaving Langdon and

moving several yards to a portable table covered with investigation tools, cables, and

assorted electronic gear. “As I told you,” he said, rummaging around the table, “we have

touched nothing. Are you familiar with this kind of pen?”

Langdon knelt down farther to see the pen's label.

STYLO DE LUMIERE NOIRE.

He glanced up in surprise.

The black-light pen or watermark stylus was a specialized felt-tipped marker originally

designed by museums, restorers, and forgery police to place invisible marks on items.

The stylus wrote in a noncorrosive, alcohol-based fluorescent ink that was visible only

under black light. Nowadays, museum maintenance staffs carried these markers on their

daily rounds to place invisible “tick marks” on the frames of paintings that needed

restoration.

As Langdon stood up, Fache walked over to the spotlight and turned it off. The gallery

plunged into sudden darkness.

Momentarily blinded, Langdon felt a rising uncertainty. Fache's silhouette appeared,

illuminated in bright purple. He approached carrying a portable light source, which

shrouded him in a violet haze.

“As you may know,” Fache said, his eyes luminescing in the violet glow, “police use

black-light illumination to search crime scenes for blood and other forensic evidence. So

you can imagine our surprise . . .” Abruptly, he pointed the light down at the corpse.

Langdon looked down and jumped back in shock.

His heart pounded as he took in the bizarre sight now glowing before him on the

parquet floor. Scrawled in luminescent handwriting, the curator's final words glowed

purple beside his corpse. As Langdon stared at the shimmering text, he felt the fog that

had surrounded this entire night growing thicker.

Langdon read the message again and looked up at Fache. “What the hell does this

mean!”

Fache's eyes shone white. “That, monsieur, is precisely the question you are here to

answer.”

Not far away, inside Saunière's office, Lieutenant Collet had returned to the Louvre and

was huddled over an audio console set up on the curator's enormous desk. With the

exception of the eerie, robot-like doll of a medieval knight that seemed to be staring at

him from the corner of Saunière's desk, Collet was comfortable. He adjusted his AKG

headphones and checked the input levels on the hard-disk recording system. All systems

were go. The microphones were functioning flawlessly, and the audio feed was crystal

clear.

Le moment de vérité, he mused.

Smiling, he closed his eyes and settled in to enjoy the rest of the conversation now

being taped inside the Grand Gallery.