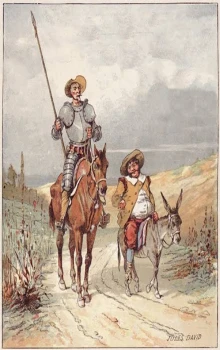

OF THE PLEASANT DISCOURSE THAT PASSED BETWEEN DON QUIXOTE AND HIS

SQUIRE SANCHO PANZA

Now by this time Sancho had risen, rather the worse for the handling of

the friars' muleteers, and stood watching the battle of his master, Don

Quixote, and praying to God in his heart that it might be his will to grant

him the victory, and that he might thereby win some island to make him

governor of, as he had promised. Seeing, therefore, that the struggle was

now over, and that his master was returning to mount Rocinante, he ap-

proached to hold the stirrup for him, and, before he could mount, he went

on his knees before him, and taking his hand, kissed it saying, "May it

please your worship, Senor Don Quixote, to give me the government of that

island which has been won in this hard fight, for be it ever so big I feel my-

self in sufficient force to be able to govern it as much and as well as anyone

in the world who has ever governed islands."

To which Don Quixote replied, "Thou must take notice, brother Sancho,

that this adventure and those like it are not adventures of islands, but of

cross-roads, in which nothing is got except a broken head or an ear the less:

have patience, for adventures will present themselves from which I may

make you, not only a governor, but something more."

Sancho gave him many thanks, and again kissing his hand and the skirt

of his hauberk, helped him to mount Rocinante, and mounting his ass him-

self, proceeded to follow his master, who at a brisk pace, without taking

leave, or saying anything further to the ladies belonging to the coach, turned

into a wood that was hard by. Sancho followed him at his ass's best trot, but

Rocinante stepped out so that, seeing himself left behind, he was forced to

call to his master to wait for him. Don Quixote did so, reining in Rocinante

until his weary squire came up, who on reaching him said, "It seems to me,

senor, it would be prudent in us to go and take refuge in some church, for,

seeing how mauled he with whom you fought has been left, it will be no

wonder if they give information of the affair to the Holy Brotherhood and

arrest us, and, faith, if they do, before we come out of gaol we shall have to

sweat for it."

"Peace," said Don Quixote; "where hast thou ever seen or heard that a

knight-errant has been arraigned before a court of justice, however many

homicides he may have committed?"

"I know nothing about omecils," answered Sancho, "nor in my life have

had anything to do with one; I only know that the Holy Brotherhood looks

after those who fight in the fields, and in that other matter I do not meddle."

"Then thou needst have no uneasiness, my friend," said Don Quixote,

"for I will deliver thee out of the hands of the Chaldeans, much more out of

those of the Brotherhood. But tell me, as thou livest, hast thou seen a more

valiant knight than I in all the known world; hast thou read in history of any

who has or had higher mettle in attack, more spirit in maintaining it, more

dexterity in wounding or skill in overthrowing?"

"The truth is," answered Sancho, "that I have never read any history, for I

can neither read nor write, but what I will venture to bet is that a more dar-

ing master than your worship I have never served in all the days of my life,

and God grant that this daring be not paid for where I have said; what I beg

of your worship is to dress your wound, for a great deal of blood flows from

that ear, and I have here some lint and a little white ointment in the

alforjas."

"All that might be well dispensed with," said Don Quixote, "if I had re-

membered to make a vial of the balsam of Fierabras, for time and medicine

are saved by one single drop."

"What vial and what balsam is that?" said Sancho Panza.

"It is a balsam," answered Don Quixote, "the receipt of which I have in

my memory, with which one need have no fear of death, or dread dying of

any wound; and so when I make it and give it to thee thou hast nothing to

do when in some battle thou seest they have cut me in half through the mid-

dle of the body—as is wont to happen frequently,—but neatly and with

great nicety, ere the blood congeal, to place that portion of the body which

shall have fallen to the ground upon the other half which remains in the sad-

dle, taking care to fit it on evenly and exactly. Then thou shalt give me to

drink but two drops of the balsam I have mentioned, and thou shalt see me

become sounder than an apple."

"If that be so," said Panza, "I renounce henceforth the government of the

promised island, and desire nothing more in payment of my many and faith-

ful services than that your worship give me the receipt of this supreme

liquor, for I am persuaded it will be worth more than two reals an ounce

anywhere, and I want no more to pass the rest of my life in ease and hon-

our; but it remains to be told if it costs much to make it."

"With less than three reals, six quarts of it may be made," said Don

Quixote.

"Sinner that I am!" said Sancho, "then why does your worship put off

making it and teaching it to me?"

"Peace, friend," answered Don Quixote; "greater secrets I mean to teach

thee and greater favours to bestow upon thee; and for the present let us see

to the dressing, for my ear pains me more than I could wish."

Sancho took out some lint and ointment from the alforjas; but when Don

Quixote came to see his helmet shattered, he was like to lose his senses, and

clapping his hand upon his sword and raising his eyes to heaven, be said, "I

swear by the Creator of all things and the four Gospels in their fullest ex-

tent, to do as the great Marquis of Mantua did when he swore to avenge the

death of his nephew Baldwin (and that was not to eat bread from a table-

cloth, nor embrace his wife, and other points which, though I cannot now

call them to mind, I here grant as expressed) until I take complete

vengeance upon him who has committed such an offence against me."

Hearing this, Sancho said to him, "Your worship should bear in mind,

Senor Don Quixote, that if the knight has done what was commanded him

in going to present himself before my lady Dulcinea del Toboso, he will

have done all that he was bound to do, and does not deserve further punish-

ment unless he commits some new offence."

"Thou hast said well and hit the point," answered Don Quixote; and so I

recall the oath in so far as relates to taking fresh vengeance on him, but I

make and confirm it anew to lead the life I have said until such time as I

take by force from some knight another helmet such as this and as good;

and think not, Sancho, that I am raising smoke with straw in doing so, for I

have one to imitate in the matter, since the very same thing to a hair hap-

pened in the case of Mambrino's helmet, which cost Sacripante so dear."

"Senor," replied Sancho, "let your worship send all such oaths to the dev-

il, for they are very pernicious to salvation and prejudicial to the con-

science; just tell me now, if for several days to come we fall in with no man

armed with a helmet, what are we to do? Is the oath to be observed in spite

of all the inconvenience and discomfort it will be to sleep in your clothes,

and not to sleep in a house, and a thousand other mortifications contained in

the oath of that old fool the Marquis of Mantua, which your worship is now

wanting to revive? Let your worship observe that there are no men in ar-

mour travelling on any of these roads, nothing but carriers and carters, who

not only do not wear helmets, but perhaps never heard tell of them all their

lives."

"Thou art wrong there," said Don Quixote, "for we shall not have been

above two hours among these cross-roads before we see more men in ar-

mour than came to Albraca to win the fair Angelica."

"Enough," said Sancho; "so be it then, and God grant us success, and that

the time for winning that island which is costing me so dear may soon

come, and then let me die."

"I have already told thee, Sancho," said Don Quixote, "not to give thyself

any uneasiness on that score; for if an island should fail, there is the king-

dom of Denmark, or of Sobradisa, which will fit thee as a ring fits the fin-

ger, and all the more that, being on terra firma, thou wilt all the better enjoy

thyself. But let us leave that to its own time; see if thou hast anything for us

to eat in those alforjas, because we must presently go in quest of some cas-

tle where we may lodge to-night and make the balsam I told thee of, for I

swear to thee by God, this ear is giving me great pain."

"I have here an onion and a little cheese and a few scraps of bread," said

Sancho, "but they are not victuals fit for a valiant knight like your worship."

"How little thou knowest about it," answered Don Quixote; "I would

have thee to know, Sancho, that it is the glory of knights-errant to go with-

out eating for a month, and even when they do eat, that it should be of what

comes first to hand; and this would have been clear to thee hadst thou read

as many histories as I have, for, though they are very many, among them all

I have found no mention made of knights-errant eating, unless by accident

or at some sumptuous banquets prepared for them, and the rest of the time

they passed in dalliance. And though it is plain they could not do without

eating and performing all the other natural functions, because, in fact, they

were men like ourselves, it is plain too that, wandering as they did the most

part of their lives through woods and wilds and without a cook, their most

usual fare would be rustic viands such as those thou now offer me; so that,

friend Sancho, let not that distress thee which pleases me, and do not seek

to make a new world or pervert knight-errantry."

"Pardon me, your worship," said Sancho, "for, as I cannot read or write,

as I said just now, I neither know nor comprehend the rules of the profes-

sion of chivalry: henceforward I will stock the alforjas with every kind of

dry fruit for your worship, as you are a knight; and for myself, as I am not

one, I will furnish them with poultry and other things more substantial."

"I do not say, Sancho," replied Don Quixote, "that it is imperative on

knights-errant not to eat anything else but the fruits thou speakest of; only

that their more usual diet must be those, and certain herbs they found in the

fields which they knew and I know too."

"A good thing it is," answered Sancho, "to know those herbs, for to my

thinking it will be needful some day to put that knowledge into practice."

And here taking out what he said he had brought, the pair made their

repast peaceably and sociably. But anxious to find quarters for the night,

they with all despatch made an end of their poor dry fare, mounted at once,

and made haste to reach some habitation before night set in; but daylight

and the hope of succeeding in their object failed them close by the huts of

some goatherds, so they determined to pass the night there, and it was as

much to Sancho's discontent not to have reached a house, as it was to his

master's satisfaction to sleep under the open heaven, for he fancied that each

time this happened to him he performed an act of ownership that helped to

prove his chivalry.